It’s not often one gets a chance to visit far-flung parts of the world for work when you’re in higher education; so as part of the development funds I received for my National Teaching Fellowship, I decided to earmark a couple of international conferences. The Higher Education Teaching and Learning conference was the first of these: organised by the US-based HETL Portal, this year’s conference was taking place in Anchorage, Alaska.

Two things were immediately attractive: the location (I’d never visited Alaska but am a big fan of mountains, snow and lakes – and Northern Exposure*), but more importantly, that very location meant that it was attracting participants from every continent: access being easy for Asia and Australasia as much as North and South America. What better chance to get an overview of current issues in higher education across the world?

Two things were immediately attractive: the location (I’d never visited Alaska but am a big fan of mountains, snow and lakes – and Northern Exposure*), but more importantly, that very location meant that it was attracting participants from every continent: access being easy for Asia and Australasia as much as North and South America. What better chance to get an overview of current issues in higher education across the world?

And so it proved. The attendees were a fascinating mix of senior learning and teaching staff (pro-VCs and equivalent) with innovative and highly engaged ‘regular’ teachers: so whilst one of the spacious, discursive sessions might present 3-4 fascinating case studies of innovative teaching; the next would feature a prolonged discussion around organisational strategy: a perfect professional development experience, on all levels.

Highlights were many, and aided by the edict that there could be no powerpoint (or digital) materials: it was voice and handouts only. This shifted many sessions into very thoughtful narratives or interactive events; with a handful spoiling this by discovering a rogue projector and reverting to reading off their slides. Those who thought about this ‘limitation’, though, delivered. Colin Potts (Georgia Tech., USA) started the conference with a bang by calling HE a ‘blip’ on the lifelong learning landscape: noting that this is the first generation who can’t say “I don’t know” (Google being constantly to hand), and that students are forced by HE to study a narrow subject path, when they are naturally more widely interested. John Doherty and Walter Nolan (Northern Arizona, USA) then guided us in a lively and discursive workshop around engaging colleagues in creative curriculum design: a conversation from which led to a more relaxed discussion of institution-level curriculum planning with Frank Coton (Vice-Principle Learning & Teaching at Glasgow) over a beer and looking out at the Alaskan mountains from the venue’s 15th-floor “chart room”.

A view of snowy mountains in every direction

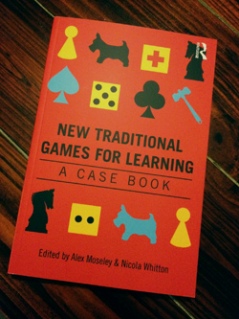

The following day saw a number of examples of the use of video to engage and support students – in ‘flipped classroom’ approaches and as co-created artefacts for peer support. I presented as part of a session focussed on games-based learning, which drew a large group and resulted in an excellent discussion after the four different, but all interesting, papers (aided, perhaps, by my imported Cadbury’s prizes). iPad use featured heavily in other sessions: my research colleague Claire Hamshire (Manchester Metropolitan) describing her use of iPads for medical teaching; Carrie Moore and Vicki Stieha (Boise State, USA) assigning group roles to students using iPads in a research exercise – and finding that students, when given a clear role, self-policed the group much more effectively; and Kriya Dunlap (Alaska Fairbanks) gave out iPads to his students with initial guidance, but then left them to work out the most effective use for their studies – they ended up co-publishing a paper together on the processes. This latter example is a similar approach to that we’re using with our Medicine first years, to similar positive effect.

A session on institutional change for learning technologies featured some fabulous methods and approaches, such as providing video booths for students to drop in and voice their needs and frustrations (e.g.. “I want my timetable on my smartphone”): which the senior management were so affected by that they implemented a major overhaul of all institutional systems – and staff development plans – to focus on student needs (Brian Webster, Edinburgh Napier). Frederic Fovet (McGill, Canada) described his institution’s application of Universal Design for Learning (UDF) which designs curricula from an inclusive base (so that the whole curriculum is naturally accessible to all). Another fascinating paper came from Jeffrey Schnepp (Bowling Green State, USA) and Christian Rogers (Indiana/Purdue, USA) who used a Professor Layton style method of trading hints for points in end of year exams: students could opt to trade a percentage of the available mark for a hint about the question, on a question by question basis. Their trial is ongoing, but initial results showed a small increase in the average grade, with around 70% of students opting for at least one hint.

There were too many other interesting sessions, discussions and informal chats to mention: in many ways it was a never-ending wave of engaging topics. Conversations went on long into the night, too, courtesy of the midnight sun (the sky looked as if it was noon, around 11pm) and some very good Anchorage restaurants: and even after the conference finished we were still discussing the topics over coffee (finishing with a fascinating chat to David Giles – Flinders, Australia – about focussing on playfulness and the ability to fail, in learning design).

To get the best flights, I was left with a day and half after the conference to explore some of the fantastic scenery around Alaska, and joined Claire and others on a jaw-droppingly-beautiful train journey down to the port at Seward, where we boarded a boat to view whales and other sea life. The following day, we hiked up one of Anchorages smaller mountains, Flattop Mountain, which was still quite a serious climb, rewarded with snow to trample at the top.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Altogether, HETL 2014 and Alaska made for an amazing, once-in-a-lifetime experience: a fabulous conference, fascinating people, and stunning place. I feel both privileged and humbled to have been part of it.

*Northern Exposure, it turns out, was actually filmed in New York state; and contrary to the strap line, I saw no moose on any corner.